The Philippines has a rich and complex history spanning over 700,000 years. This timeline presents the full story of how the Philippine nation developed from its prehistoric beginnings through colonial periods to its current status as an independent democratic republic. Understanding Philippine history helps explain the culture, traditions, and identity of modern Filipinos.

Prehistoric Philippines: The Dawn of Human Settlement

Early Human Presence (709,000 BCE to 50,000 BCE)

The earliest evidence of human activity in the Philippines dates back to approximately 709,000 years ago, when the first Homo species arrived during the early Chibanian period. Archaeological discoveries show that Homo erectus set foot on the Philippine islands around 400,000 BCE. These early humans likely reached the archipelago during periods of lower sea levels when land bridges connected various islands.

In 2018, researchers discovered butchered rhinoceros bones on Luzon island with clear marks of stone tools, suggesting human presence as early as 700,000 years ago. The makers of these tools were likely related to Homo erectus, who had the basic technological capabilities for such work. However, these early populations arrived not through intentional navigation but possibly via natural rafts during typhoons.

The Tabon Cave People (50,000 BCE to 20,000 BCE)

Around 50,000 BCE, early humans created stone tools in the Tabon Caves in Palawan. The famous Tabon Man, whose remains date to approximately 20,000 BCE, made stone tools and lived in these cave systems. Archaeological evidence from Tabon Cave shows that these prehistoric inhabitants engaged in basket making and rope making using plant fibers between 39,000 and 33,000 years ago.

The Tabon Caves provided shelter and resources for early human communities, who survived by hunting, gathering, and fishing. Their tools were simple and irregularly shaped, made primarily from stone and designed for immediate use,

Arrival of the Negritos (40,000 BCE)

Dark-skinned, short-statured, and frizzy-haired peoples called Negritos or Aytas reached the archipelago around 40,000 BCE. These groups migrated from southern China to escape dangerous predators and found the Philippine jungles relatively hospitable. The Negritos were the first anatomically modern humans to settle in the Philippines and represent an important part of the archipelago's genetic and cultural heritage.

Austronesian Migration and Cultural Development

The Great Austronesian Expansion (4,500 BCE to 300 BCE)

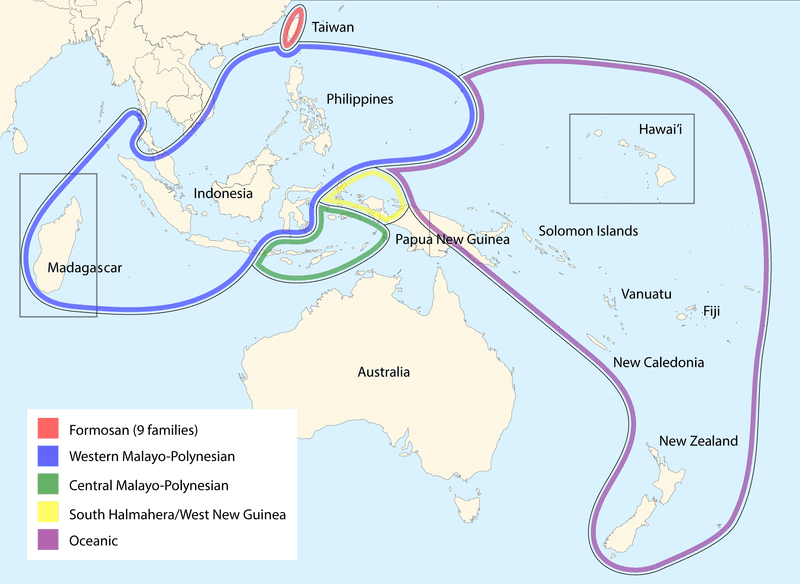

Between 4,500 BCE and 300 BCE, multiple waves of Austronesian-speaking peoples migrated from Taiwan to the Philippines. These seafaring people brought revolutionary changes, including rice cultivation, domestication of chickens and pigs, and advanced boat-building techniques. The Austronesians arrived in the Batanes Islands, the northernmost Philippines, around 2200 BCE.

Research indicates that the Amis people of eastern Taiwan are the closest relatives to Malayo-Polynesian communities, including modern Filipinos. These migrants used sails before 2000 BCE and developed sophisticated maritime technologies, including catamarans and outrigger boats. Their expansion ultimately reached locations as distant as Madagascar to the west and Easter Island to the east.

Neolithic Advances (4,000 BCE to 1,000 BCE)

By 4,000 BCE, the earliest evidence of rice growing and animal domestication appears in the Philippines. Communities began creating permanent settlements, particularly near water sources that facilitated travel and trade. Around 3,000 BCE, ancient Filipinos created the Angono Petroglyphs, rock carvings that still exist in Rizal province.

The Late Neolithic period brought significant advances, including the creation of the Yawning Jarlet found in Leta-leta caves in Palawan, which became a national treasure. By 600 BCE, people in Palawan, the Cordillera region, and Batanes became skilled goldsmiths, creating the famous lingling-o or omega-shaped gold ornaments.

Pre-Colonial Kingdoms and Sultanates

The Laguna Copperplate Inscription (900 CE)

April 21, 900 CE marks the official end of Philippine prehistory with the creation of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription. Written in Kawi script, this document is the earliest known written record from the Philippines. The inscription proves that by 900 CE, Philippine communities had established trade networks and political systems influenced by Hindu-Buddhist cultures from Southeast Asia.

Kingdom of Tondo (900 CE to 1571)

The Kingdom of Tondo emerged as one of the most powerful pre-colonial polities in Luzon, flourishing along the Pasig River and Manila Bay shores. Tondo engaged in extensive trade with China as early as 900 CE and exerted influence over modern-day Laguna, Bulacan, and Pampanga. The kingdom was ruled by a Lakan, and by the time of Spanish arrival, Lakandula was one of the last prominent rulers.

Tondo's power came from its strategic location and commercial networks. The relationship between Tondo and neighboring polities resembled an alliance system between senior and junior partners rather than a feudal hierarchy.

Rajahnate of Cebu (13th Century to 1565)

The Rajahnate of Cebu served as an important trading hub between the sultanates of Mindanao, the Kingdom of Borneo, and the Chinese Empire. Founded by Sri Lumay, a minor prince from Sumatra, Cebu grew into a major political power. When Ferdinand Magellan arrived in 1521, Rajah Humabon ruled as the undisputed leader of Cebu.

Cebu controlled strategic trade routes through the Visayas region and maintained diplomatic and commercial relationships across the archipelago. The kingdom's wealth came from maritime trade in gold, pearls, and other valuable commodities.

Sultanate of Sulu (1405 to 1915)

Founded on November 17, 1405, by Sharif ul-Hashim, the Sultanate of Sulu became a powerful maritime state. Islam first reached the Philippines in 1380 when Muslim traders arrived in Sulu and Jolo. The sultanate controlled the Sulu Archipelago, coastal areas of Zamboanga, portions of Palawan, and parts of Sabah and North Kalimantan in Borneo.

The Sultanate of Sulu maintained close ties with the broader Muslim community in Southeast Asia and the Kingdom of Borneo. Spanish colonizers feared Sulu's powerful pirate fleets that controlled the Celebes Sea. The sultanate maintained political independence until 1915, when it signed the Carpenter Agreement with the United States.

Sultanate of Maguindanao (15th Century to 19th Century)

Established by Shariff Mohammed Kabungsuwan, the Sultanate of Maguindanao successfully resisted Spanish colonization for centuries. Under Sultan Kudarat, who ruled from 1619 to 1671, Maguindanao became a formidable power that defended against Spanish incursions. The sultanate also influenced the Maranao states near Lake Lanao, spreading Islam throughout the region.

Rajahnate of Butuan (10th Century to 16th Century)

The Rajahnate of Butuan in Mindanao was described by Spanish chroniclers as extraordinarily wealthy, with houses decorated with gold and even servants wearing gold jewelry. Butuan ranked among the richest states not just in the Philippine archipelago but throughout Southeast Asia. The kingdom engaged in active trade with China and other regional powers.

Spanish Colonial Period: Christianization and Conquest

Magellan's Arrival (March 16, 1521)

Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese navigator leading a Spanish expedition, reached the Philippine archipelago on March 16, 1521. The expedition first sighted Zamal, now known as Samar, after months at sea. On uninhabited Homonhon island, Magellan's crew found fresh water and rested before making contact with local inhabitants.

Magellan named the archipelago the islands of St. Lazarus, celebrating the feast day that coincided with their arrival. The chronicler Antonio Pigafetta documented these historic encounters in detail. On March 31, 1521, the first Easter Sunday Mass in the Philippines was celebrated at Limasawa Island.

The Battle of Mactan (April 27, 1521)

Magellan's expedition met a violent end at the Battle of Mactan on April 27, 1521. Ferdinand Magellan led a small Spanish force to subdue the chieftain Lapulapu, who ruled Mactan island. The battle resulted in a disastrous defeat for the Europeans due to the overwhelming number of Lapulapu's forces and tactical disadvantages faced by the heavily armored Spaniards in shallow coastal waters.

Lapulapu's victory at Mactan made him the first Filipino hero to resist foreign colonization. Surviving members of Magellan's crew continued the expedition under Juan Sebastian de Elcano, who completed the first circumnavigation of the globe in September 1522.

Spanish Conquest Under Philip II (1565 to 1571)

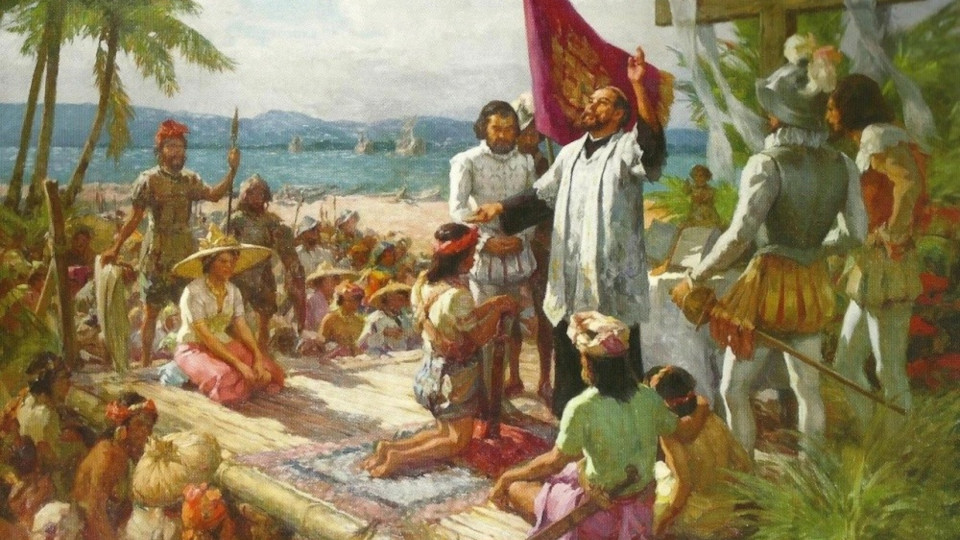

Permanent Spanish colonization began in earnest in 1564 when Miguel López de Legazpi led an expedition that arrived in Cebu on February 13, 1565. Despite initial Cebuano opposition, Legazpi conquered the island and established Spanish control. The expedition included only 500 men but received support from Augustinian friars who began converting Filipinos to Christianity.

In 1567, Spanish and Mexican soldiers founded Fuerza de San Pedro at Cebu as a military stronghold for protection against native resistance and Muslim pirates. On June 23, 1569, Spain officially took possession of the archipelago.

In 1570, Legazpi sent his grandson Juan de Salcedo to conquer Maynila. Following a larger force comprising Spanish and Visayan troops, Legazpi renamed Maynila as Nueva Castilla and declared it the capital of the Philippines and the Spanish East Indies on June 24, 1571. This marked the beginning of Spanish colonial rule that would last over 300 years.

Colonial Administration and Society (1571 to 1898)

Spain ruled the Philippines through a governor-general appointed by the Spanish crown. The colonial government introduced the encomienda system, which required the local population to pay tribute and perform labor. Spanish missionaries established churches, schools, hospitals, and universities throughout the archipelago.

The Spanish colonial period brought dramatic changes to Filipino society. Catholic missionaries converted most lowland inhabitants to Christianity, though Muslim communities in Mindanao and Sulu maintained their Islamic faith. The Spaniards consolidated dispersed barangays into towns to facilitate administration and religious conversion.

Spanish rule also introduced the galleon trade, connecting Manila with Acapulco in Mexico. This trade route brought Asian goods to the Americas and American silver to Asia, making Manila a crucial link in global commerce. However, Spanish colonial policies also created social inequalities and economic exploitation that would eventually fuel revolutionary movements.

The Philippine Revolution and Independence

Rise of Filipino Nationalism (1880s to 1896)

By the late 19th century, Filipino intellectuals and reformists began advocating for greater rights and representation within the Spanish empire. José Rizal, a physician and writer, became the movement's most prominent voice through his novels Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo. Spanish authorities executed Rizal on December 30, 1896, making him a martyr for the independence cause.

The Katipunan (July 7, 1892)

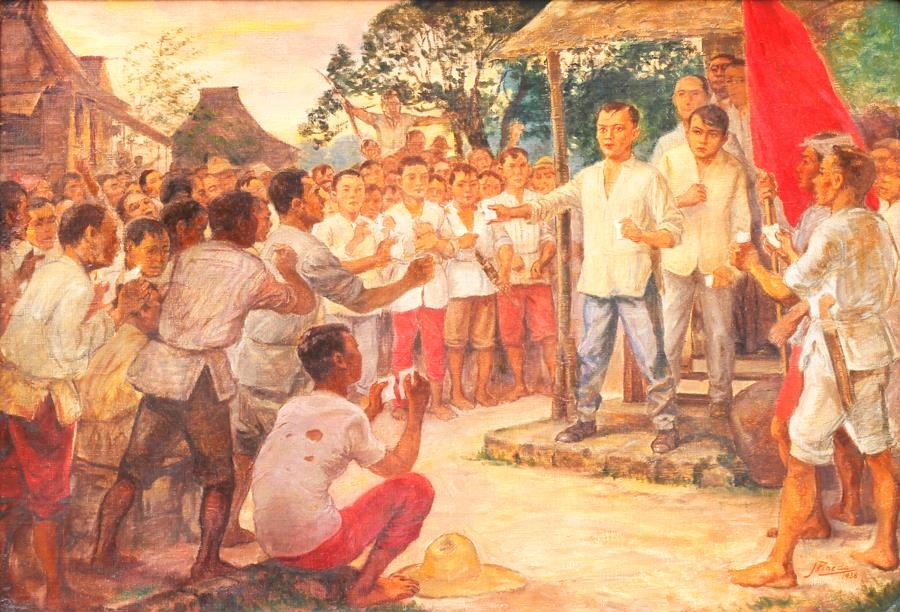

Andrés Bonifacio, Deodato Arellano, Ladislao Diwa, Teodoro Plata, and Valentín Díaz founded the Katipunan in Manila on July 7, 1892. The full name, Kataas-taasang, Kagalang-galangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan, translates to Supreme and Venerable Society of the Children of the Nation.

The organization advocated independence through armed revolt against Spain. It was forged by blood, with members enacting traditional blood compacts and signing their names with their own blood. The Katipunan recruited extensively from peasants and the working class, eventually gaining between 30,000 and 400,000 members by 1896.

The Cry of Balintawak (August 23 to 26, 1896)

On August 19, 1896, Spanish authorities discovered the Katipunan, forcing Bonifacio to launch the revolution prematurely. Between August 23 and 26, 1896, Bonifacio called Katipunan members to Balintawak for a mass gathering. During this event, revolutionaries tore their cedulas or community tax certificates, symbolizing their rejection of Spanish colonial oppression.

The exact date and location remain disputed, with the Philippine government officially recognizing August 23 in Pugad Lawin. This event marked the beginning of the nationwide armed revolution against Spain.

The Philippine Republic (June 12, 1898)

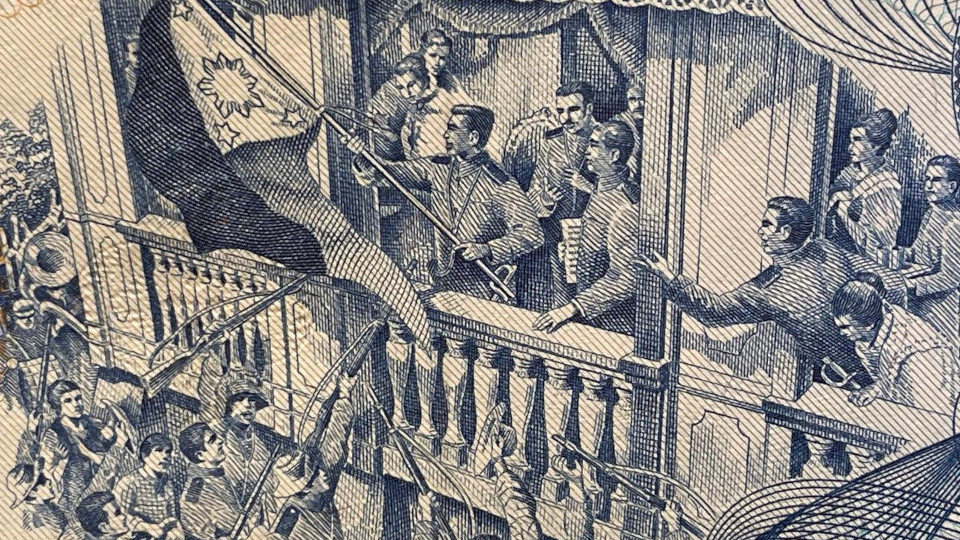

|

| Image from The Kahimyang Project |

On June 12, 1898, General Emilio Aguinaldo proclaimed Philippine independence from Spain at his ancestral home in Cavite el Viejo, now Kawit, Cavite. Between four and five in the afternoon, Aguinaldo displayed the new national flag, played the national anthem, and declared the Philippines free from Spanish rule.

Ambrosio Rianzares Bautista prepared, wrote, and read the Act of Declaration of Independence in Spanish. The proclamation was signed by 98 people, including a United States Army officer who witnessed the proceedings. On August 1, 1898, 190 municipal presidents from 16 provinces ratified the Declaration of Independence in Bacoor, Cavite.

However, neither the United States nor Spain recognized this declaration. The struggle for true independence would continue for decades.

Spanish American War and American Colonization

The Battle of Manila Bay (May 1, 1898)

On May 1, 1898, Commodore George Dewey led the US Asiatic Squadron in the Battle of Manila Bay, decisively defeating Spanish naval forces. This victory occurred during the Spanish American War and marked the beginning of American involvement in the Philippines.

Prior to the battle, Dewey transported Aguinaldo back to the Philippines aboard the USS McCulloch on May 19, 1898. Aguinaldo believed the Americans would support Philippine independence similar to Cuba's treatment. The Americans provided weapons and encouraged Filipino forces to continue fighting against Spain.

Treaty of Paris (December 10, 1898)

The Treaty of Paris, signed on December 10, 1898, officially ended the Spanish American War. Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States for 20 million dollars. This agreement ignored the Philippine Republic that Aguinaldo had established and treated the islands as property to be transferred between colonial powers.

Filipino revolutionaries had expected American recognition of their independence but instead faced a new colonial master. The treaty's terms sparked outrage among Filipinos who had fought for freedom from Spain.

Philippine American War (1899 to 1902)

On February 4, 1899, the Philippine American War erupted after US troops fired on Philippine forces in Manila. This conflict proved brutal, with American forces employing harsh tactics to suppress Filipino resistance. Philippine troops initially attempted conventional warfare but shifted to guerrilla tactics after ten months of unsuccessful battles.

The war resulted in devastating casualties. An estimated 250,000 to 1 million Filipino civilians died, mostly from famine and disease. American forces used reconcentration policies, tortured prisoners, and devastated civilian property to defeat the insurgency.

General Miguel Malvar surrendered on April 16, 1902, marking the official end of the war. However, resistance continued in some regions for several more years, particularly among Muslim communities in Mindanao and Sulu.

American Colonial Administration (1898 to 1946)

The United States established military government in the Philippines on August 14, 1898. Beginning in 1906, civilian government replaced military administration under the Insular Government structure. William Howard Taft served as the first civil governor general.

American colonial policy focused on education, infrastructure development, and gradual preparation for self government. The Americans established a public school system using English as the medium of instruction. This policy dramatically increased literacy rates but also replaced Spanish with English as the islands' primary international language.

In 1916, the Jones Act promised eventual independence and established a bicameral Philippine Legislature. This represented the first major step toward self governance under American rule.

The Philippine Commonwealth (1935 to 1946)

The Tydings McDuffie Act of 1934 created the Commonwealth of the Philippines as a transitional government leading to full independence in ten years. Manuel L. Quezon won the first presidential election and took office on November 15, 1935.

Quezon implemented significant reforms during his administration. He established the Institute of National Language, declaring Tagalog the basis for a national language on December 30, 1937. Women gained suffrage in 1937 after a successful plebiscite. The Commonwealth government also pursued agrarian reform and economic development programs.

The Commonwealth period brought political stability and economic growth. However, World War II and Japanese invasion would interrupt the path to independence, postponing the scheduled date of July 4, 1946.

World War II and Japanese Occupation

Japanese Invasion (December 8, 1941)

Japan invaded the Philippines on December 8, 1941, just ten hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Japanese aircraft severely damaged American planes at Clark Field near Manila in the initial attack. Lacking air cover, the American Asiatic Fleet withdrew to Java on December 12, 1941.

General Douglas MacArthur ordered American and Filipino forces to retreat to the Bataan Peninsula ahead of the Japanese advance. Manila was declared an open city to prevent its destruction, but Japanese forces occupied it by January 2, 1942. President Quezon and Vice President Sergio Osmeña evacuated to Corregidor Island before eventually fleeing to the United States in March 1942.

The Fall of Bataan and Corregidor (April to May 1942)

The 76,000 starving and sick American and Filipino defenders in Bataan surrendered on April 9, 1942. Japanese forces then forced these prisoners to march 65 miles to prison camps in what became known as the infamous Bataan Death March. Between 7,000 and 10,000 prisoners died or were murdered during this march.

The 13,000 survivors on Corregidor Island surrendered on May 6, 1942. These defeats marked the complete Japanese conquest of the Philippines. However, Filipino resistance never ceased, with guerrilla forces continuing to fight throughout the occupation.

Japanese Occupation (1942 to 1945)

Japan occupied the Philippines for over three years. The occupation brought tremendous suffering to Filipinos through forced labor, military atrocities, and economic exploitation. Japanese forces pressed large numbers of Filipinos into work details and forced young Filipino women into military brothels.

The Japanese established a puppet government headed by José Laurel in October 1943, declaring the Philippines independent. However, this government had no real authority and served only Japanese interests.

Filipino guerrilla forces controlled approximately sixty percent of the islands, mostly in forested and mountainous areas. General MacArthur supplied these resistance fighters by submarine and sent reinforcements and officers to coordinate their efforts. The Filipino population remained generally loyal to the United States because of the American promise of independence and their suffering under Japanese rule.

Liberation of the Philippines (1944 to 1945)

General MacArthur fulfilled his promise to return to the Philippines on October 20, 1944, landing on Leyte with a force of 700 vessels and 174,000 troops. The liberation campaign then proceeded to Mindoro, Luzon, and Mindanao.

The Battle of Manila from February to March 1945 resulted in devastating urban destruction. Japanese forces conducted systematic massacres of civilians during their retreat, killing approximately 100,000 people in Manila alone. Around 500,000 Filipinos died during the entire liberation campaign.

The Japanese Imperial Army officially surrendered in Baguio City on August 15, 1945. September 2, 1945, marked the official liberation of the Philippines from Japanese occupation.

The Third Philippine Republic

Independence Day (July 4, 1946)

The Philippines officially gained independence on July 4, 1946, when President Harry S. Truman issued Proclamation 2695. The Treaty of Manila, signed the same day, recognized Philippine sovereignty and established formal diplomatic relations between the two countries.

Manuel Roxas, who won the first post war presidential election, became the first president of the independent Third Republic. The Commonwealth officially ended with this transfer of power. However, independence came with significant strings attached through economic agreements that favored American interests.

President Manuel Roxas (1946 to 1948)

Manuel Roxas faced enormous challenges rebuilding the war devastated nation. The economy lay in ruins, with Manila heavily damaged and infrastructure destroyed throughout the islands. Roxas accepted substantial American assistance to fund reconstruction efforts.

During his brief presidency, Roxas signed agreements allowing the United States to lease military bases including Subic Naval Base and Clark Air Base for 99 years. He also confronted the growing communist insurgency led by the Hukbalahap, or Huks, who gained strength in rural areas.

Roxas died suddenly on April 15, 1948, at Clark Air Base, just two years after independence. Vice President Elpidio Quirino succeeded him as president.

President Elpidio Quirino (1948 to 1953)

Elpidio Quirino inherited both the presidency and the problems facing the young republic. The Huk insurgency intensified during his administration as communist guerrillas gained support among impoverished peasants.

The 1949 presidential election became notorious as the Dirty Election of 1949 due to widespread electoral fraud and suppression of opposition. Despite these problems, Quirino won re election and implemented beneficial economic policies and social welfare programs, including Social Security.

Quirino contributed Philippine troops to the United Nations force during the Korean War, demonstrating the country's commitment to international cooperation. However, corruption and violence plagued his administration.

President Ramon Magsaysay (1953 to 1957)

Ramon Magsaysay decisively defeated Quirino in the 1953 election, receiving 68 percent of the vote. A former defense secretary under Quirino, Magsaysay ran under the Nacionalista Party and became the first president to wear the traditional Barong Tagalog.

Magsaysay's administration is remembered as a golden era for the Philippine economy. He successfully dismantled the Huk insurgency by promising land reform to peasants and addressing the root causes of rural discontent. Magsaysay also opened Malacañang Palace to ordinary citizens, demonstrating his commitment to accessible government.

Despite his popularity and achievements, Magsaysay's presidency ended tragically when his plane crashed in Cebu on March 16, 1957, killing 25 of 26 passengers. The nation mourned the loss of one of its most beloved leaders.

President Carlos P. Garcia (1957 to 1961)

Vice President Carlos Garcia was sworn in as president the day after Magsaysay's death. Garcia introduced the Filipino First Policy, which prioritized Filipino entrepreneurs over foreign investors in economic development.

Garcia also signed the Bohlen Serrano Agreement, reducing the lease period for American military bases from 99 years to 25 years. This represented a significant assertion of Philippine sovereignty. However, Garcia lost his re election bid in 1961 to his own vice president, Diosdado Macapagal.

President Diosdado Macapagal (1961 to 1965)

Diosdado Macapagal's presidency achieved important reforms despite facing allegations of corruption and political favoritism. His most significant accomplishment was the Agricultural Land Reform Code of 1963, which abolished tenancy and initiated land redistribution.

Macapagal officially changed Independence Day from July 4 to June 12, commemorating the 1898 declaration by Aguinaldo rather than the 1946 American grant of independence. This symbolic change emphasized Philippine nationalism and the sacrifices of revolutionary heroes.

The Stonehill Scandal involving American businessman Harry Stonehill's alleged bribery of Filipino politicians damaged Macapagal's reputation. He lost the 1965 presidential election to Ferdinand Marcos.

The Marcos Era and Martial Law

President Ferdinand Marcos (1965 to 1972)

Ferdinand Marcos began his presidency in 1965, winning election under the Nacionalista Party. During his first term, Marcos pursued infrastructure development and economic growth programs.

However, the 1969 campaign involved massive government spending that severely damaged the economy. By the early 1970s, the Philippines faced balance of payments crisis, rising inflation, and increasing social unrest.

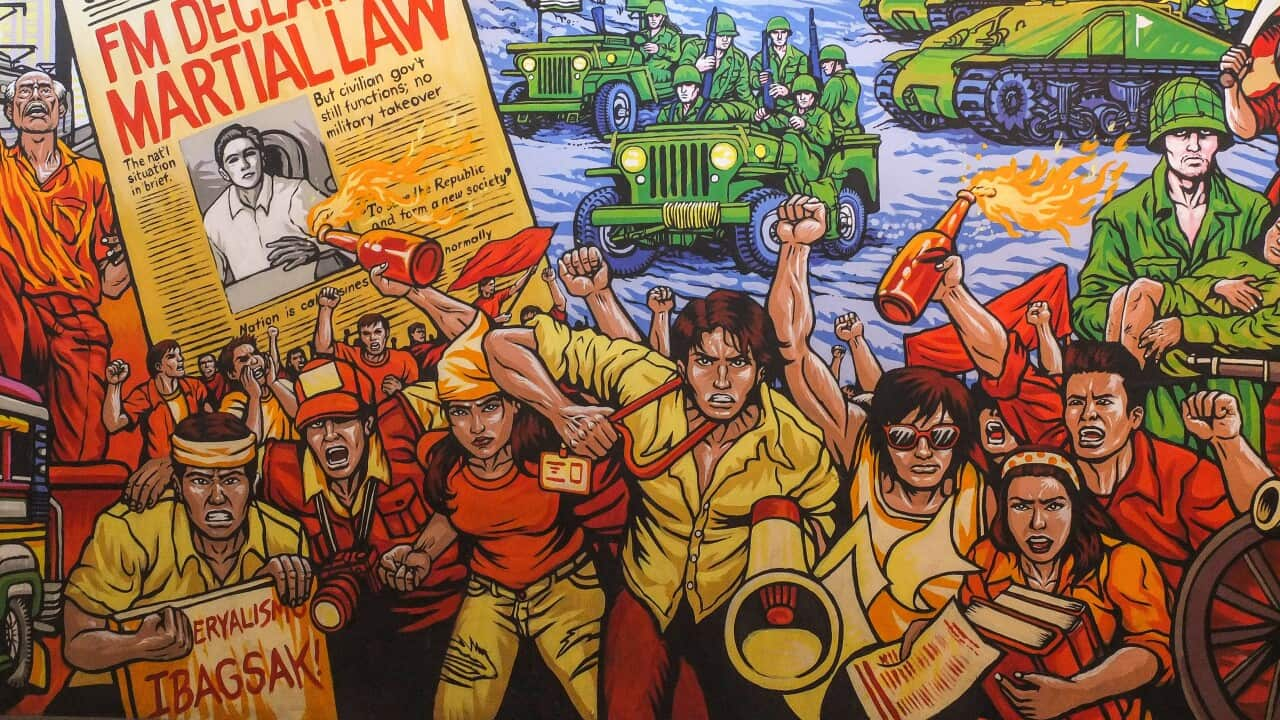

Declaration of Martial Law (September 21, 1972)

On September 21, 1972, Marcos signed Proclamation 1081, placing the Philippines under martial law. He announced this decision to the public on September 23, 1972. Marcos claimed martial law was necessary to address communist insurgency, Muslim separatism, and widespread disorder.

Critics accused Marcos of exaggerating threats to consolidate power and extend his rule beyond constitutional limits. The 1935 Constitution prohibited presidents from serving more than two terms, but martial law allowed Marcos to remain in power indefinitely.

The Martial Law Years (1972 to 1981)

The martial law period witnessed systematic human rights abuses. The Marcos dictatorship was marked by thousands of extrajudicial killings, documented cases of torture, enforced disappearances, and incarcerations.

Marcos arrested opposition politicians, student activists, journalists, and religious workers. He shut down media outlets and declared new elections unnecessary. The dictatorship also allowed the Marcos family to accumulate massive unexplained wealth through corruption.

Marcos formally lifted martial law on January 17, 1981. However, he retained essentially all dictatorial powers until his ouster in 1986. The lifting of martial law was largely cosmetic, designed to improve international perception without changing the authoritarian nature of the regime.

The EDSA People Power Revolution

The Assassination of Ninoy Aquino (August 21, 1983)

Senator Benigno Ninoy Aquino Jr., Marcos's most prominent critic, was assassinated on August 21, 1983, at Manila International Airport. Aquino had returned from exile in the United States despite warnings that his life was in danger. His murder shocked the nation and galvanized opposition to the Marcos regime.

Ninoy's widow, Corazon Cory Aquino, emerged as the leader of the opposition movement. Her moral authority as the widow of a martyred hero gave her unique standing to challenge Marcos.

The Snap Election (February 7, 1986)

Under pressure from the United States and opposition groups, Marcos called for a snap presidential election to be held on February 7, 1986. Corazon Aquino ran against Marcos with former Senator Salvador Laurel as her running mate.

The election was marked by massive fraud and violence. Despite clear evidence that Aquino had won, the Marcos controlled Batasang Pambansa proclaimed Marcos and his running mate Arturo Tolentino as the winners. This blatant electoral theft triggered calls for massive civil disobedience.

The Four Days That Changed History (February 22 to 25, 1986)

On February 22, 1986, Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile and Lieutenant General Fidel V. Ramos announced their defection from the Marcos administration at Camp Aguinaldo. They had been planning a coup, but their plot was discovered, forcing them to act prematurely.

Manila Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin broadcast an appeal on Radyo Veritas, calling on citizens to support Enrile and Ramos by surrounding Camp Aguinaldo and Camp Crame with protective human barriers. Thousands of Filipinos responded, converging on Epifanio de los Santos Avenue, commonly known as EDSA.

Over the next four days, more than two million Filipino civilians gathered on EDSA. They faced down tanks and armed soldiers through nonviolent resistance, prayer, and determination.

Military units began defecting to the opposition. When loyalist forces prepared to attack with tear gas and weapons, soldiers refused orders to fire on the unarmed civilians. This moment of moral courage by military personnel proved decisive.

On February 25, 1986, Corazon Aquino was sworn in as president at Club Filipino in San Juan. Just hours later, Ferdinand Marcos fled to Hawaii with his family, ending his 21 year rule. The peaceful revolution became known worldwide as People Power and inspired similar movements in other countries.

Conclusion:

The Philippine story spans over 700,000 years of human presence, cultural development, colonial struggles, and nation building. From the prehistoric settlements in Tabon Cave to the modern democracy of today, Filipino history demonstrates resilience, adaptability, and a continuous struggle for freedom and dignity.

Understanding this complex history helps explain contemporary Philippine society, culture, and politics. The colonial experiences under Spain and America shaped Filipino identity, language, religion, and institutions. The revolutionary movements against Spain, America, and Japan forged a national consciousness. The struggle against the Marcos dictatorship and the peaceful EDSA Revolution demonstrated the power of nonviolent resistance.

Today's Philippines faces both opportunities and challenges. Economic growth offers the potential to lift millions out of poverty and establish the nation as a major regional power. Democratic institutions, though sometimes fragile, provide mechanisms for peaceful political change. The young, educated population represents enormous potential for future development.

However, persistent problems demand attention. Political dynasties concentrate power and wealth in elite families. Corruption undermines public services and economic development. Regional conflicts, particularly in Mindanao, require continued peace building efforts. Income inequality creates social tensions and limits opportunities for many Filipinos.

The complete timeline of Philippine history reveals patterns of resilience and adaptation. Filipinos have repeatedly overcome tremendous challenges through unity, creativity, and determination. By understanding this history, Filipinos and friends of the Philippines can build on past achievements while avoiding past mistakes. The story of the Philippines continues to unfold, shaped by the choices and actions of each new generation.